Remote Setting (Part 2)

John W. McCabe

Remote Setting Tanks (C. gigas)

Some type of open, large vat or pool, hereafter called a tank,

is essential in remote setting. Remote setting tanks, simply

called setting tanks by growers, come in various sizes,

shapes and designs. Numerous materials have been used in their

construction. Fiberglass, stainless steel and concrete tanks

are the most common. Whatever the material used in tank construction,

it is imperative that it does not emit toxins when remote setting

is attempted. The same applies to any accessories (e.g. PVC aeration

pipes, hoses) that come in contact with the water in the setting

tanks. Hidden toxin sources are certain sealants that retain

"superior flexibility" and, worse yet, are "mildew

resistant". Instead, any sealant in contact with the water

of such a cultivation environment should be "aquarium safe".

It is common knowledge in the shellfish industry that even minute

toxin amounts can negatively affect larval setting. As such,

newly constructed fiberglass and concrete tanks and accessories

must first thoroughly "cure" before use. In some cases,

this can take several months. Some stainless alloys can also

be problematic.

Ironically, as annoying as later scrubbing countless renegade

spat off the sidewalls of a setting tank is, it is an endorsement

of its functionality.

Most setting tanks are operated outside. Some tanks are insulated.

While there is no such thing as a "standard

setting tank", they all have features in common. An oyster

grower that employs remote setting will typically own one or

more setting tanks that work well with the cultivation method

he or she employs (e.g. ground/bottom cultivation, longline cultivation).

It must hold a sufficient amount of weathered oyster shells (cultch)

in a way that is conducive for larvae to distribute and affix

themselves as evenly in quantity as possible to the individual

shells provided.

The saltwater in setting tanks usually originates from a marine

environment close-by, typically the grower's leased or owned

tideland. To aid the distribution of larvae, the water in the

setting tanks is agitated, often by bubbling with oil-less compressed

air through perforated PVC pipes. In most cases, the water is

heated and maintained at about 20 to 25° C (68 to 77°

F). Seawater in setting tanks can be heated in numerous ways

(e.g. electric, oil, propane, natural gas heaters or passive

solar heating). All setting tanks must be thoroughly cleaned

after use. This includes scrubbing off spat that has glued itself

to side-walls instead of the offered cultch. Some growers use

stainless steel wool to aid in tank-cleanup.

Depending on the size and number of tanks

and methodology employed, the remote setting process can last

about one to two weeks (excluding any additional marine preconditioning

of cleaned cultch). Cleaning of the setting tanks and accessories

before and after is essential. Some growers add microalgae to

their tanks before, during, and/or after the setting. How much

remote setting a grower engages in is usually based on that grower's

projected oyster production in coming years. It need not be done

all at once. In the course several months, the same tanks may

be used repeatedly to produce more spatted cultch. In the North-American

Pacific Northwest, remote setting commonly starts in early spring

and, in some cases, may continue at intervals until early summer.

Cultch

The word cultch (also

culch) describes a wide variety of objects, naturally

occurring or manmade, that are utilized for their appeal to larval

or post-larval bivalves as attachment and early grow-out surfaces.

In some cases, the alternate term spat collector(s) is

preferred. In oyster cultivation, weathered oyster shells are

traditionally the preferred type of cultch.

Inset

image: Large transporter dumping oyster shells from shucking

facilities for natural weathering.

Inset

image: Large transporter dumping oyster shells from shucking

facilities for natural weathering.

Oyster growers have long known that oyster

larvae love to cement themselves to oyster shells. Many oyster

growers on the North-American West Coast and in Asia process

Pacific/Japanese oysters for their meat only (called shucking),

meaning that these oyster are not destined for the half-shell

market (i.e. where oysters are slurped raw off the half-shell).

Once the meat is extracted, the growers save the shells. Oyster

growers then allow them to weather in huge piles on land for

later use. These mounds of fresh shells from a shucking facility

are of great interest to birds, bugs and bacteria. They immediately

start stripping every last bit of oyster meat left on the shells.

The sun and wind gradually desiccate the shells. The freshwater

from rain gently erodes the calcium carbonate. The organic matrix

of the shells also gradually dries, thus reducing structural

impact resilience. About two years later, the oyster shells are

lighter and have structurally weakened. At this point, they can

be considered cultch. Lighter shell weight presents a

little advantage in their transport. More importantly, however,

years later, when spat on these shells has grown and turned each

one into a massive clusters of live oysters, the somewhat weakened

old shells help in the process of breaking the oyster clusters

apart (called culling).

Before usage, the cultch is often fed through

a trommel (from the German word Trommel, meaning

drum). The trommel separates debris (small shell fragments, soil,

leaves etc) from the shells. The shells are then typically washed

with  pressurized water and packed into

synthetic mesh bags or other, similarly webbed containers.

pressurized water and packed into

synthetic mesh bags or other, similarly webbed containers.

Inset image: A 40 ft (~ 12 m) commercial flatbed trailer loaded

with a shipment of clean cultch, parked at the Coast Seafoods

hatchery in Quilcene, Washington State. Clean cultch is commonly

packed in polyethylene mesh sacks (e.g. Vexar) which can be stacked

like 4 ft logs for transport. Click image for a closer look.

Inset image: Example of a crisscross

stack. In remote setting, polyethylene mesh sacks can effectively

be stacked in a crisscross fashion, akin to the way logs can

be stacked when building a campfire. Stacking cultch in this

manner allows good water circulation and optimizes shell surface

exposure for the attachment of oyster larvae.

Inset image: Example of a crisscross

stack. In remote setting, polyethylene mesh sacks can effectively

be stacked in a crisscross fashion, akin to the way logs can

be stacked when building a campfire. Stacking cultch in this

manner allows good water circulation and optimizes shell surface

exposure for the attachment of oyster larvae.

In preparation for remote setting, some growers further condition

the clean cultch by temporary submersion in bay water. Doing

so will thinly coat the shells with so called biofilm,

a rather nondescript word that describes a slippery, organic

coating that usually includes bacteria. It is believed that a

measured amount of biofilm can be attractive to oyster larvae

that are ready to attach themselves and may possibly be of nutritional

significance. Other growers do not further condition their cultch

in this manner. Instead, the clean cultch is directly offered

to the larvae. Although both methods can work well, neither guarantees

a "good set" because various other factors come into

play (e.g. water circulation, temperature, water quality, larval

condition). It is to be expected as normal that many of the oyster

larvae will die before ever attaching themselves to the shells.

Many more will die during metamorphosis and still more will die

soon thereafter. In practice this means that only a small fraction

of the larvae in the aforementioned pouches will reach a marketable

oyster size.

Once the shells are populated with spat, they are called spatted

cultch.

Set and Spatcount

The noun set describes

visible evidence on marine surfaces, especially cultch, of an

aggregation of oysters or other bivalves that have very recently

completed metamorphosis.

Oyster growers rate sets (e.g. very good, good, light, poor or

no set) on the basis of the average spat population found on

surfaces in a given area, typically the surfaces of oyster shells

(i.e. the spat found on a flat or cupped valve). For example,

after remote setting, averaging the numbers of spat found on

50 to 100 shells sampled from various areas of a setting tank

will yield the spatcount.

Inset image:

The shell portion on the left (approx. 10 cm or 4")

shows early post-larval Pacific oysters at about three weeks

from setting. In remote setting, the set on this shell is excessive

(so called spray paint). As these oysters grow, they will

compete for space while continuously building their shell. Many

will have stunted or malformed shells. Most will not survive.

Click image for enlargement.

Inset image:

The shell portion on the left (approx. 10 cm or 4")

shows early post-larval Pacific oysters at about three weeks

from setting. In remote setting, the set on this shell is excessive

(so called spray paint). As these oysters grow, they will

compete for space while continuously building their shell. Many

will have stunted or malformed shells. Most will not survive.

Click image for enlargement.

In remote setting of oysters, a "very

good set" typically describes an average of 15 to 30 firmly

cemented post-larval oysters (i.e. the spatcount) that

are distributed fairly evenly per oyster shell. Some growers

and hatcheries prefer 20 to 40. A shell with just six to ten

spat, evenly distributed, is a "light set" that can

ultimately still yield a very nice return after the oysters have

grown. A "poor set" in remote setting are shells that

average less than five spat per shell. Although it seems reasonable

to conclude that hundreds of spat per shell would be cause for

celebration in remote setting, many oyster growers would instead

be quite displeased. Hundreds of spat per shell is called called

spray paint. Crowded spat on shells leads to mass mortality

and tangled, dense clusters of oysters of varying size, many

with malformed shells. When faced with such abundant sets, some

growers have tediously broken the spatted shells into smaller

pieces to later give the growing oysters more room to develop

their shells more freely.

Assessments of sets in remote setting differ

from assessments in "wild sets". The aforementioned

"spray paint" can actually be welcome among bottom

cultivating growers that depend on bountiful wild sets on the

cultch they have tediously spread on their cultivation grounds.

In North-America, the Pacific (or Japanese) oyster used to be

principally valued as a cooking oyster, not as a raw, half-shell

oyster. As such, it was the meat that mattered, not the shape

of the shell. Big, gnarly clusters of oddly shaped, fat oysters

thus spelled profit. This has changed in recent decades. Although

Pacific oysters are still in demand as meat oysters, they are

now also prized as half-shell oysters. In the lucrative half-shell

trade, the shell size and shape matters greatly.

"No set" indicates that all the

money, time and work invested in offering cultch to wild larvae

was for naught. Even if a few wild spat turn up (which is commonly

the case), it is still deemed "no set", because so

few spat are not nearly enough to support a grower's business.

The daunting uncertainty associated with wild sets has plagued

oyster growers worldwide for many centuries. It is the underlying

reason for today's existence of remote setting.

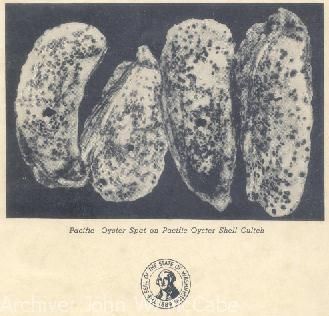

Inset

image: Photo of heavily spatted shells on the cover of the State

of Washington Dept. of Fisheries Biological Report No. 43A, 1943.

This rare report furnishes details on Washington State's 1942

spawning and setting of the Japanese oyster, renamed as the "Pacific

oyster" (then still scientifically known as Ostrea gigas).

The image is titled Pacific Oyster Spat on Pacific Oyster

Shell Cultch. Each shell features well over one hundred wild

spat. They were the result of natural oyster spawning events

at an unspecified location in western Washington. The great quantity

of wild spat per shell qualified as a "very good set".

1942 was a special year for the oyster industry on the North

American West Coast. It was the first year in decades that saw

no Japanese oyster seed shipments (spatted cultch) as both Canada

and the United States were at war with Japan. Fortunately, Pacific

oysters successfully spawned at a never before seen rate during

the war years. The absence of Japanese seed supply was thus easily

bridged with greatly improved, local seed production. At the

same time, Japanese-American oyster growers and their families

were sent to internment camps and usually lost their livelihoods.

Inset

image: Photo of heavily spatted shells on the cover of the State

of Washington Dept. of Fisheries Biological Report No. 43A, 1943.

This rare report furnishes details on Washington State's 1942

spawning and setting of the Japanese oyster, renamed as the "Pacific

oyster" (then still scientifically known as Ostrea gigas).

The image is titled Pacific Oyster Spat on Pacific Oyster

Shell Cultch. Each shell features well over one hundred wild

spat. They were the result of natural oyster spawning events

at an unspecified location in western Washington. The great quantity

of wild spat per shell qualified as a "very good set".

1942 was a special year for the oyster industry on the North

American West Coast. It was the first year in decades that saw

no Japanese oyster seed shipments (spatted cultch) as both Canada

and the United States were at war with Japan. Fortunately, Pacific

oysters successfully spawned at a never before seen rate during

the war years. The absence of Japanese seed supply was thus easily

bridged with greatly improved, local seed production. At the

same time, Japanese-American oyster growers and their families

were sent to internment camps and usually lost their livelihoods.

Example of Remote Setting in a Large Setting Tank

Example of Remote Setting in a Large Setting Tank

The inset image shows a fiberglass setting tank, one of three,

located at the Olympia Oyster Company (click image to enlarge).

With a capacity of 28,350 liters (7,500 gallons) it qualifies

as a large setting tank. Larger setting tanks exist. The setting

tanks at this grower's facility are not insulated. The pictured

tank is about 12 years old. Despite repeated, seasonal usage

and year-round outdoor exposure, the tanks appear as sturdy today

as the day they were built. The size, rectangular design and

support framing suggests that any one of these tanks could, if

needed, be moved elsewhere with moderate preparation. Sturdy

planking surrounds each tank. It provides good footing when working

at waist-height anywhere along the upper, inside edge of the

tanks in a standing position. A heavy gauge, steel frame rises

above each tank. On the frame, a strong, steel overhead rail

can be seen, centered and running lengthwise above the tank.

When in use, the rail is extended to two more steel supports

mounted on a heavy timber bulkhead at the edge of the bay. This

rail serves to facilitate mechanical lowering and hoisting of

heavy cultch containers in and out of the tank and, after remote

setting, moving the cultch containers onto a barge at high tide.

All the setting tanks have industrial lighting fixtures for night-time

work. Seawater from the adjacent bay is pumped into the tank(s)

and then warmed by diesel oil boiler heat-pipes.

The pictured view

of the inside of the setting tank shows the heat pipes and two

long, white PVC pipe grates resting on the tank's edge. The PVC

pipes are perforated. During remote setting, these grates lie

flat on the bottom of the tank with the cultch on top. During

operation, compressed air from an oil-less electric blower motor

is pumped through the perforated pipes. Subsequent bubbling vigorously

agitates the tank water.

The pictured view

of the inside of the setting tank shows the heat pipes and two

long, white PVC pipe grates resting on the tank's edge. The PVC

pipes are perforated. During remote setting, these grates lie

flat on the bottom of the tank with the cultch on top. During

operation, compressed air from an oil-less electric blower motor

is pumped through the perforated pipes. Subsequent bubbling vigorously

agitates the tank water.

Remote setting at this grower's facility

is repetitive. It may commence sometime in April and continue

until June.

For example, this grower gradually fills the clean setting tanks

with bay water on a Monday and starts warming and agitating the

water with compressed air on Tuesday and Wednesday. Historically,

much like many other oyster growing regions, the Puget Sound

region has also had occasional seawater conditions that proved

detrimental to the setting of oyster larvae and survival of spat

(e.g. blooms of certain algal species, heavy siltation). Some

growers thus filter the seawater they use for remote setting.

This grower does not. Instead, Tim McMillin, a second generation

oysterman and the longtime general manager of the Olympia Oyster

Company, visually inspects the bay's water condition for appropriate

clarity near the setting tanks before pumping the water in. Occasionally,

further inspection with a microscope is necessary. He has worked

this bay since early childhood and knows it intimately - including

its highly variable water conditions.

On Thursday, containers filled with clean cultch are added. Several

small, meshed testing bags with cultch are also added in various

areas of each tank. The clean cultch is not preconditioned in

the bay prior to use (i.e. no light biofilm is provided). On

Friday, remote setting is initiated by adding the larvae to the

warmed, agitated water in the setting tank. No microalgae feed

is added to the water at any point. On the following Monday,

the small, meshed bags with cultch are pulled for examination.

Microscopic inspection of numerous shells provides an approximate

spatcount and also shows the condition of the spat. Ideally,

the shell of each spat should appear flat and well affixed to

the cultch (i.e. the spat's shell should not be angled). On Tuesday,

the spatted cultch in the containers is pulled from the tanks

and moved to an intertidal location. Here, the spat will continue

to grow. Some growers cover their spatted cultch out on their

tideland with tarps to protect it from various environmental

threats (e.g. heat, birds). This grower does not. After each

remote setting session, the tanks are scrubbed clean. Typically,

some spat has stubbornly set on the sidewalls of the tanks and

pipes. It is scrubbed off with stainless steel wool.

The Olympia Oyster Company used to operate five large setting

tanks. When I took some of the above pictures, they operated

three. At the time of this writing, they only operate two large

setting tanks and have disposed of the rest. This is because

the shellfish business changes as time goes on and all shellfish

growers must adjust accordingly. The Olympia Oyster Company used

to continuously shuck a large volume of oysters for meat (both

Pacific oysters and petite Olympia oysters, Ostrea lurida).

Much remote setting was necessary to produce sufficient amounts

of Pacifc oysters for meat processing. In recent years, this

company has greatly reduced its shucking and instead shifted

some of its resources into producing more Pacific oyster shell

stock for resale (sizes extra small to large) and expanding tumbler

cultivation of their very popular boutique oysters called Kobachii

- and all the while still maintaining their classic Olympia oyster

cultivation (no longer shucked because Olympia oysters are in

high demand as half-shell oysters). Due to increasing demand,

the Olympia Oyster Company also expanded its Manila and native

littleneck clam cultivation.

The unusually tasty shellfish this company

consistently produces has not been a well kept secret. It has

been my impression over the course of many years that their wholesale

business is consistently brisk.

Details on the Cultch Containers

Details on the Cultch Containers

In remote setting, the Olympia

Oyster Company does not use polyethylene mesh sacks filled with

cultch. Instead, they use large, specially designed cultch containers

that are shaped like a cube with meshing on all sides and also

chambered with mesh on the inside (click image to enlarge). This

insures good flow-through of water. Moreover, the design prevents

restrictive compacting of the shells and, a few months later,

allows for easy dumping of the more matured spatted cultch directly

onto tideland. These cultch containers will be moved twice. Firstly,

they are used for the remote setting process by lowering them

into the water filled setting tanks on top of the perforated

PVC pipe grates used for water agitation by aeration. A few days

thereafter, the containers are pulled and placed on a barge to

then be deposited on tideland in a chosen area in the intertidal

zone. A few months later, depending on the rate of further development

of the spat, these containers are moved again to another section

of the company's tideland, typically of lower intertidal elevation,

for further grow-out. The design of the containers allows removal

of sections to prevent the shells from binding-up when spreading

the spatted cultch directly onto the tideland.

Each cultch container is lifted by polyethylene rope secured

on top at all four corners.

Details on Pitching the Larvae

Details on Pitching the Larvae

I like to refer to the adding of the oyster larvae to setting

tanks as "pitching the larvae" because it reminds me

of "pitching the yeast" when I make wine and beer.

We now return to the aforementioned "tennis balls"

that each hold six million oyster larvae. The first step is to

open such a pouch full of larvae and inspect its contents. It

should not smell "fishy". The larvae ball can easily

be broken in half. The inside should appear moist, not dried

out. Half of the ball, give or take, is placed into a small bucket

that

is filled about half-way with warmed water from the setting tank.

When gently swishing the larval clump around in the bucket, it

readily dissolves into what looks a bit like clear bouillon soup.

This "larval soup" is then carefully and evenly poured

onto the surface of one half of the setting tank. This procedure

is repeated with the remainder of the larvae in the pouch on

the other half of the setting tank. Just a few days from this

moment, microscopically small specs, the spat, will be evident

on the cultch.

Inset

image: Oyster larvae being evenly "pitched" during

remote setting. Please note the now extended top rail above the

setting tank leading to a heavy timber bulkhead at the edge of

the bay. Please also note the exposed tideland (low tide) beyond

the bulkhead. When the remote setting process is completed, a

barge can conveniently load the cultch containers at the bulkhead

at high tide.

Part

1 Part 2

William

Firth Wells, Growing Oysters Artificially, The Conservationist,

1920, 3(10), pp 151 -154

William

Firth Wells, Growing Oysters Artificially, The Conservationist,

1920, 3(10), pp 151 -154

Herbert

F. Prytherch, Experiments in the Artificial Propagation of

Oysters, Dept. of Commerce, Bureau of Fisheries, Doc. No.

961, 1924

Herbert

F. Prytherch, Experiments in the Artificial Propagation of

Oysters, Dept. of Commerce, Bureau of Fisheries, Doc. No.

961, 1924

Herbert

F. Prytherch, The Cultivation of Lamellibranch Larvae,

found in 1959 reprint by Dover Publications of Culture Methods

for Invertebrate Animals (1937, Comstock Publishing Co.), pp.

539 - 542

Herbert

F. Prytherch, The Cultivation of Lamellibranch Larvae,

found in 1959 reprint by Dover Publications of Culture Methods

for Invertebrate Animals (1937, Comstock Publishing Co.), pp.

539 - 542

William

K. Brooks, The Oyster, The Johns Hopkins Press, Baltimore,

1891

William

K. Brooks, The Oyster, The Johns Hopkins Press, Baltimore,

1891

Paul Simon Galtsoff, The

American Oyster Crassostrea Virginica, United States Dept.

of the Interior, Fish and Wildlife Service, Bureau of Commercial

Fisheries, Fishery Bulletin, Volume 64, printed by the United

States Government Printing Office, Washington, 1964

Paul Simon Galtsoff, The

American Oyster Crassostrea Virginica, United States Dept.

of the Interior, Fish and Wildlife Service, Bureau of Commercial

Fisheries, Fishery Bulletin, Volume 64, printed by the United

States Government Printing Office, Washington, 1964

Victor

L. Loosanoff & Harry C. Davis, Rearing of Bivalve Mollusks,

U.S. Bureau of Commercial Fisheries, 1963

Victor

L. Loosanoff & Harry C. Davis, Rearing of Bivalve Mollusks,

U.S. Bureau of Commercial Fisheries, 1963

Jerry

E. Clark & R. Donald Langmo, Oyster Seed Hatcheries on

the U.S. West Coast: An Overview, Oregon State University,

Sea Grant College Program, 1979

Jerry

E. Clark & R. Donald Langmo, Oyster Seed Hatcheries on

the U.S. West Coast: An Overview, Oregon State University,

Sea Grant College Program, 1979

Herbert

Hidu, Samuel R. Chapman and David Dean,

Herbert

Hidu, Samuel R. Chapman and David Dean,

Oyster Mariculture in Subboreal (Maine, United States of America)

Waters: Cultchless Setting and Nursery Culture of European and

American Oysters 1, JOURNAL OF SHELLFISH RESEARCH,

June 1981, Vol. 1, No. 1, pp. 57-67

https://fisheries.btc.ctc.edu/Manuals/Remote%20Setting%20of%20Oyster%20Larvae.pdf

https://fisheries.btc.ctc.edu/Manuals/Remote%20Setting%20of%20Oyster%20Larvae.pdf

Also found at:

https://www.innovativeaqua.com/Publication/Pub1.htm