The Belle Époque

John McCabe

After many decades of military altercations in Europe, the Treaty

of Frankfurt on May 10th, 1871, finally brought some peace for

a few decades. The ensuing decades are today loosely referred

to as the "Belle Époque". It lasted right

up to the summer of 1914, when Germany declared war on France

and the horrors of WW I began.

The Worlds Fair of 1889 in Paris was exemplary

of the Belle Époque. Thirty million visitors got a glimpse

of what the future would likely bring. It was a grand event.

The fairgrounds were electrically lit up until midnight for the

first time. The setting must have seemed surreal to most visitors.

Amazed crowds would delight in viewing countless fascinating

displays of entertainment, science and technology. An engineer

by the name of Gustave Eiffel had managed to have 7 million holes

drilled into 15,000 steel plates. He then had them all screwed,

bolted and welded together. The resulting 7,000 ton steel tower,

famous today all over the world as the Eiffel Tower, seemed to

practically touch the sky above. Like a huge, ominous index finger

pointing 984 feet up into the air, it boldly prophesized the

future: "The sky's the limit!".

The Belle Époque was a fantastic

time period. Optimism, excitement, free thinking, ingenuity and

invention, and the promise of a better life with more prosperity

abounded. It was simply a celebration of mankind. All the best

bits and pieces of mankind's past trials and tribulations seemed

to have finally come together. The arts, literature, sciences,

and technology all blossomed beautifully. Even a guy by the name

of Charles Darwin, who,in 1859, dared to challenge the biblical

story of creation with a new evolutionary theory, became mandatory

reading for many - at a time, when Darwin had already long left

the public circuit and chosen a life of semi-reclusivity. One

new invention was chased by the next and industry was flourishing

unbridled in Europe and America. In 1816, the United States had

issued a mere 3,000 patents. By 1896, the height of the Belle

Époque, this figure had risen to 56,000.

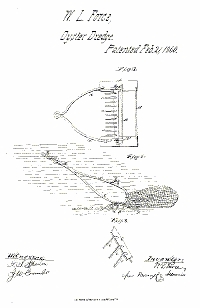

The spirit of invention was also alive and well

in the American oyster industry. Pictured we see a '"new

and improved" oyster dredge, patented by Wm. L. Force in

1860. The dredge had a sled design. A steel bar with strong teeth,

reminiscent of a massive garden rake, scooped up the oysters

and fed them into a steel link bag located behind it. While the

French were already forging towards the perfection of oyster

cultivation, the Americans were perfecting oyster exploitation.

By 1920, huge American oyster steamers with crews of 25 men were

dragging many of these dredges simultaneously. A typical oyster

steamer of this size could harvest 8,000 bushels of oysters per

day.

The spirit of invention was also alive and well

in the American oyster industry. Pictured we see a '"new

and improved" oyster dredge, patented by Wm. L. Force in

1860. The dredge had a sled design. A steel bar with strong teeth,

reminiscent of a massive garden rake, scooped up the oysters

and fed them into a steel link bag located behind it. While the

French were already forging towards the perfection of oyster

cultivation, the Americans were perfecting oyster exploitation.

By 1920, huge American oyster steamers with crews of 25 men were

dragging many of these dredges simultaneously. A typical oyster

steamer of this size could harvest 8,000 bushels of oysters per

day.

Although poverty was still wide spread,

a large and most affluent business class evolved alongside the

nobles, which rejoiced in spending lots money on "the  finer things

in life". Oysters were, of course, a big part of these "finer

things", as was Champagne. Champagne, the "King of

Wines", and the oyster, the "Queen of the Sea",

were celebrated as a match made in heaven. Many discreet little

establishments called "Séparées"

started popping up in and around Paris, which served oysters

and Champagne for breakfast, lunch and dinner. Champagne houses

were making money hand over fist during these decades. Oysters

were being consumed at record levels. Ornate three-pronged oyster

forks and finely crafted oyster plates and platters with beautiful

hand-painted motifs became fashionable components of tableware

sets. Sterling silver oyster forks and French porcelain oyster

platters of the Belle Époque and the first half of the

20th century, are highly prized collectibles today.

finer things

in life". Oysters were, of course, a big part of these "finer

things", as was Champagne. Champagne, the "King of

Wines", and the oyster, the "Queen of the Sea",

were celebrated as a match made in heaven. Many discreet little

establishments called "Séparées"

started popping up in and around Paris, which served oysters

and Champagne for breakfast, lunch and dinner. Champagne houses

were making money hand over fist during these decades. Oysters

were being consumed at record levels. Ornate three-pronged oyster

forks and finely crafted oyster plates and platters with beautiful

hand-painted motifs became fashionable components of tableware

sets. Sterling silver oyster forks and French porcelain oyster

platters of the Belle Époque and the first half of the

20th century, are highly prized collectibles today.

This French post card series from the Belle

Époque is most interesting and amusing (post cards can

be clicked for enlargement):

The post card series is titled Joyeux Réveillon

("Joyous Midnight Repast"). A dashing young man presents

a charming young lady with an oyster. But what kind?

Voila. These are Portuguese oysters (Pacific

oysters did not exist in France when these post cards were made).

The dashing young man chose Portuguese oysters instead of the

far more expensive European oysters for the lady of his dreams.

Hence, he was possibly a bit of a cheap skate. He did, however,

not skimp on the bubbly. It's real Champagne - a quite sweet

Demi-Sec to be sure. Today, the dosage of a Demi-Sec (today)

can contain a maximum of 50 grams per liter of residual sugar.

Unlike England and the United States, where drier Champagnes

(Extra-Dry, Brut, Extra-Brut) were (and are) preferred, the French,

around the turn of the century, often had a bit of a sweet tooth

when it came to Champagne. The classic "coupe design"

was often the glass of choice for Champagne during those days

(has since been replaced by flutes and tulip style glasses).

Today, dry Champagnes (and many other dry white wines) are preferred

with oysters.

He now attempts to feed the tasty mollusk

to his sweetheart - with an oyster fork. The use of an oyster

fork was considered "most civilized" during the Belle

Époque. Today, oyster forks are only rarely used with

raw oysters. Slurping the living animal off its half shell is

now considered "most civilized' as well.

Things are obviously going quite well between

these two. Only one oyster was consumed. Oddly, the rest of the

oysters remain unopened on the plate. The king of wines seems

to have taken full charge of this joyous moment.

In this final post card (at least in my

possession. There may be more...), Prince Charming moves in on

his dream girl. That lone oyster sloshing in Champagne in her

tummy seems to have made her most receptive to his advances.