|

On Oyster Knives

A good knife-maker's job is to produce knives that allow capable hands to do the job right the first time - every time! He fully understands the processing challenges that meats, vegetables, and fruits may present. Likewise, some good knife-makers also understand the obstinate oyster and other challenging types of shellfish. Producing a quality oyster knife is certainly no easy task. It must be brutishly strong, yet also very nimble. It must also be highly durable, as it is expected to be able to endure the splitting of hundreds or perhaps even thousands of "oyster rocks" in the course of many years to come. It must be light enough for a professional to work it swiftly for hours on end and not tire of its handling weight. There are two key considerations in assessing

the value of an oyster knife: Unfortunately, for the knife-maker that

is, most chefs and consumers seem unwilling to pay all that much

for a high quality oyster knife, perhaps because there is that

certain "special something" missing when one compares

an oyster knife with the fine blades often associated with star

chef cooking. To compound matters, again for the knife-maker

that is, high quality oyster knives are very rugged and built

to last. Any chef or meat-cutter gracious enough to loan out

his or her fine cutlery is doing somebody a real big favor, as

merely dropping a fine knife on the floor accidentally may ruin

it forever. Telling someone to please not drop one's oyster knife

is more likely to be interpreted as kind concern for another's

foot rather than the survival of the oyster knife. A few of my

oyster knives have been through hell and back and are still every

bit as functional as the day they were made. Hence, a good knife-maker

can't bank on all that much repeat business with his oyster knives,

at least not in terms of replacement. A new oyster knife of high

quality that is priced under US$ 20 is always a bargain - the

price of merely one dozen oysters on the half shell ordered at

a nice restaurant. The only way to beat that bargain price down

even more and still end up with a quality oyster knife is to

buy a good used one. Lady Luck is certainly on the side of bargain

shoppers in this respect, as used oyster knives, even if decades

old and the company that once made them has long since closed

its doors, are commonly still ready to shuck countless more oysters.

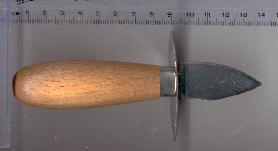

Unlike many high quality kitchen knives, quality oyster knives require low to no maintenance. The main problem is that they do have a tendency to get lost, particularly since oyster lovers frequently will not leave their favorite oyster knife behind when it's time to visit the seashore. I frequently visit state parks in pursuit of shellfish and have lost a few oyster knives over the years. I've also found a few. However, such a discovery brings me no joy, as I know how the previous owner felt after loosing it. In a way, it's a little like losing a trusted friend. Gallery Note: The ruler used in these pictures measures in centimeters. Respective knife dimensions in inches are noted with each knife. Some oyster knives have round or oval hand guards. They aim to protect the cutting hand from the sharp shell edge and also serve as a blade stop after entering the oyster. Occasional positive or negative comments on any particular knife merely reflect my personal opinion. A Frenchman  This is a French oyster knife. It is stamped INOX which qualifies the guard and blade metal as European stainless steel. The blade is short and well made. It features a large hand guard. The strong stainless steel blade is sharp on both edges with a very pointed tip. It is designed for small sized oysters. Dimensions: Blade length 2". Blade width near center point just under 1" (2 cm) and rapidly narrows towards tip (pronounced "V" design). Butt to point 6". Weight 2 oz. Another Frenchman  At the time of this writing, I don't know (yet) who in France manufactures this unmarked oyster knife (perhaps Deglon, Sabatier or Matfer Bourgeat). The box it came in was simply marked "Made in France". The knife is short, sleek, attractive looking, and very well made. The steel runs the length of the knife, from the tip to the end of the handle (called a full-tang). The wood handle is well formed. It's made up of two equal wood halves (called scales) which are secured through the shank of the blade (called the tang) with two strong brass pins. In the same manner, a third (down-sized) brass pin secures what looks like a split solid brass crown ahead of the handle (instead of the common ferrule). The sturdy stainless steel blade is sharp on one side (called the edge) and leads to a very sharp point. The top, thicker portion of the blade (called the spine) is flat. I've frequently used this knife on Kumamoto, European, and Olympia oysters. It also works well on small and extra small Eastern and extra small Pacific oysters. It is one of my personal favorites. Dimensions: Blade 3". Blade width at center point just under a ½" (1 cm) and gradually narrows towards tip. Butt to point 6.25". Weight 3 oz. Generic #1  This is a typical oyster knife style made

in a number of countries by different manufacturers. The design

usually has either a short or a long blade with a rounded or

pointed tip. The pictured knife is a long blade version with

a pointed tip. Although the basic design works well, the materials

and manufacturing quality of this type of knife can range anywhere

from junk to very good. I bought the pictured knife about 20

years ago for a buck at a yard sale. It was made in Japan, probably

manufactured in the 1960s or 70s. Its quality happens to be very

good and no doubt works as well today as it did the day it was

made - despite heavy use. The typical rounded oak handle grips

well. An oval stainless steel hand guard/blade stop separates

the blade portion from the handle. The blade is very sturdy.

Both edges of the blade are rather dull. The tip is moderately

pointed. The bottom of the blade on this knife was machined cleverly

near the tip to provide a slightly raised point (similar to the

New Haven design described further below). This is an

advantage when opening oysters via the hinge, as it provides

better leverage for breaking the hinge and, once the shell is

penetrated, helps keep the tip riding high above the tender meat

of the oyster. As mentioned, the quality and design features

of this type of knife can vary greatly these days. I've recently

come across some high quality knives of this type bearing the

name of the famed Sheffield, England. There are, however, also

lots of low quality "cheapies" out there. Caveat emptor

on this design.  Here we have a typical run of the mill import oyster knife made in "who knows where" and manufactured by "who knows". This type of knife is usually reasonably priced (pictured knife cost me about 5 bucks), cheaply made, and qualifies in my opinion as the "better than no oyster knife at all" type of oyster knife. "It works" is about all I can come up with in terms of any kind of accolades. This is the type of oyster knife I don't mind loaning out to friends and acquaintances because I really don't care whether they remember to bring it back or not. This particular one features a brown molded, hard synthetic handle that grips fairly well. Ahead of it there is a small oval hand guard/blade stop. The stainless steel blade is dull on both sides and it features a moderately pointed tip. The blade does not appear to be strong at the tang, as I can flex it easily. The start of a considerably tapered down tang leading into the handle is evident just ahead of the guard. Dimensions: Blade 3". Blade width at center point a tad over ½" (1.5 cm) and gradually narrows towards tip. Butt to point 7". Weight 2.5 oz. Generic #3  Here we have another very common design. Paying attention to manufacturing quality is certainly a prudent consideration when buying this knife type as well. Two knives of this type by different manufacturers, side by side, could look almost identical, yet one may cost less than 5 bucks and the other perhaps four to five times as much. This oyster knife design is old. Often called a "stabber", it usually features a sleek, flat, narrow blade with rather dull edges which terminates in a more or less pointed, flat point. The design is an American East Coast classic and primarily associated with the Eastern oyster. Traditionally they are used to enter oysters directly between the shell halves (called valves) either frontally or via side entry on the left or right side (when the beak of the oyster points towards opener and the cupped portion of shell is down). Good quality stabbers are very versatile and not at all limited to entry between the shell halves. Due to the most devious tip design, strong stabbers can also chop off a shell chunk at the front of the oyster (called the bill) with ease on a cutting board and finish off the oyster in seconds by entering the opening thus rendered with the tip of this knife. Equally, most strong stabbers can also function well at hinge entry on small and medium sized oysters. Many variants of this blade design evolved in the later part of the 19th century during the last decades of the oyster boom years in the American Northeast. They were christened with noble names like Chesapeake, New York, Cape Cod, Boston, and other hallow names of grand oyster locales. The blade length varies, as does the handle design. Classic oyster knives of this type feature an oval-round (as pictured) or ball shaped handle made of superior wood such as ash, some oak varieties, beech, or birch. Later designs featured a generous grip, either wooden or synthetic. The steel used today with high grade knives of this type is usually stainless 440c steel. Dimensions: Blade 4". Blade width at center point 3/8" (1 cm). Gradually starts to narrow towards tip in final inch. Butt to point 7". Weight 2 oz. Chesapeake Stabber

Boston  The names Boston, Boston stabber, Cape Cod, Cape Cod stabber describe a famous and formidable American oyster knife design. Although some design variants on the blade and handle exist, Bostons feature long, moderately narrow stainless or high carbon steel blades with long oval-round or pear shaped wooden or synthetic handles. Although some oyster knife designs are more ideally suited for certain oyster types and sizes, sturdy Bostons are marvelously versatile and very effective at opening just about any type or size of oyster with any chosen opening method (except side-knife method). They never let their owners down. This is likely the reason why it has won the hearts and minds of so many oyster lovers. The Boston pictured above is one of two types of Bostons (the other pictured below) made in the U.S. by Dexter Russell. It features a well formed synthetic handle which grips very nicely. The forward bulge in the handle serves as a stabilizing thumb rest while the more narrow body behind it enhances a good grip for the rest of the fingers. The rear of the handle is bulged again for good support in the base of the palm. This is the only kind of palmistry I'll gladly endorse. The blade is long, narrow, and strong with rather dull edges. The top and bottom of the forward section of the blade is gently convex. It gradually narrows and terminates in a flat, rounded tip. Dimensions: Blade 4". Blade width at center point just under a ½" (1.1 cm) and gradually narrows towards point. Butt to tip 8". Weight 2.5 oz.

If, by some strange circumstance, I was permitted to only keep one of my oyster knives, I'd have a terrible time choosing between my New Haven, Chesapeake and my Bostons, but would probably choose one of my Bostons (and then buy the other Bosten, another New Haven and Chesapeake stabber the very next chance I got). Galveston a.k.a. Southern a.k.a. Gulf Knife  The names Galveston, Southern, and Gulf all describe yet another famous and most formidable American oyster knife design. Just the mere sight of a Galveston must make any oyster shudder inside its shell fortress. The Galveston oyster knife is an "oyster killer" of the first order. There is nothing elegant about it. It's an excellent commercial design and means business in no uncertain terms, particularly when used in processing medium and large Eastern oysters for meat gain. Although there are some variances in design, Galvestons feature a generous wood or synthetic handle and a long, very strong, and broad blade. The Galvestons I've seen seemed virtually indestructible. The Galveston pictured above is made by Dexter Russell. The handle is the same as the one described above in the Boston description. The moderately sharp blade edges run the length of the blade. It is very gently convex (almost flat) on both the top and bottom face of the blade. There is very little narrowing of the blade width noticeable in the first 3". In the final inch, the blade narrows to a gently rounded point. Dimensions: Blade 4". Blade width at center point just under a ¾" (2.6 cm) with little narrowing up to the last inch. Butt to point 8". Weight ~ 3 oz.

New Haven  The New Haven is another famous American

oyster knife design. New Havens don't look devious like the Chesapeakes

or imposing like sturdy Bostons and Galvestons. However, please

don't let their rather short and stubby look fool you . New Havens

are superb oyster knives due to their brilliant design - particularly

when perfect oysters on the half shell are desired. Although

slight design variances exist, they feature a generous handle

with a fairly short blade. The blade has rather dull edges, the

underside is gently convex, and the top side is flat. The blade

is fairly wide and does not narrow much (or at all) for about

three-fourths of the way towards the tip. In about the last fourth

of the blade, however, the blade rapidly narrows to a sharp point.

Simultaneously, the lower convex blade side starts to elegantly

taper up to the blade point from both sides. Unlike other oyster

Crack a.k.a. Cracker  This oyster knife design is also American. Although it is obsolete by now, it certainly deserves to be mentioned, as it once was a very important shucking knife style on the North American East Coast and Gulf. Crack knives are heavy knives that offer no frills - just cold steel. Since these knives are no longer commercially used to any great extent (if at all) and most have long since gotten lost or rusted away, collectors are eager to buy this type of oyster knife. There are a great number of varying blade designs, particularly since many oystermen used to tediously make their own from plain steel bar stock. Occasionally these knives are still found along the shores of once great oystering regions on the East Coast and Gulf. Many crack designs also worked well in conjunction with a matching cracking hammer and a so called "cracking block" (old cracking or "breaking" blocks are highly collectible). Hinge (beak) forward, a (large) oyster rested against a back stop while the edge of its broad end (the bill) frequently extended a little over the edge of the block. A piece of the bill could then be knocked of with a small hammer. This produced a convenient opening for knife insertion between the shells. Shuckers would then cut the eye (shucker slang for the single adductor muscle of an oyster) with a quick twist of the wrist. A person performing this type of shucking was sometimes called a breaker. Conversely, shuckers which held the oysters with their left hand and inserted the knife between the two shells (at the bill or on the side) were called stabbers. An old pamphlet (1925) with the optimistic title "Shucking Oysters: One of New Jersey's Growing Industries (W. H. Dumont; N.J. Agricultural Experiment Stations; # 418) points out that a breaker could toss the oyster meat into a pot without ever touching it with his or her hand, while a stabber would use his or her knife and thumb to do the same. A mitten was worn on the left hand and "cots" made of rubber or canvas, on the fingers of the right. About 10 to 12 gallons of oyster meat was considered a "fair day", up to 26 gallons per day were possible. Big, fat oyster meats obviously produced a gallon fairly readily. However, a person could spend eight hard hours standing at one of many numbered wooden stations on the long shucking bench opening small oysters - and maybe achieve up to ten gallons. The shucker formula was very simple: more gallons = more money. Although old photos and postcards commonly depict white male shuckers at work, white women and Afro-American women and men (sometimes even children) constituted a (this writer actually suspects "the") major labor portion of the U.S. shucking industry in the 19th and early 20th century. Crack knives distinguish themselves as the very least ergonomic oyster knife design ever - reflective of much the rest of the U.S. oyster shucking environment of those days. They were made to last. The pictured crack (or cracker) was marketed under the once famous American trade name Carvel Hall (Briddell). The blade has dull edges and starts to narrow in the final forward 1/2 inch or so. From the rear of the blade the top and bottom very gently start tapering in and gradually join the narrowing width of the blade in the front. This forms a flat tip with a rounded shape. The heavy butt of this knife is rectangular and occasionally doubled as a culling tool (culling describes breaking up natural clusters of oysters). The butt could also be used to knock off a piece of the front of an oyster (the bill) before turning the knife around and sliding in its devious flat blade tip to cut the oyster's adductor muscle. Dimensions: Blade 4". Blade width at center point just a tad over 1/2" (1.6 cm) Blade width starts narrowing to a tip in the last ½ inch. Butt to point 8". Weight 6 oz. More Oldies Most of these old custom steel oyster knives

are no more "primitive" than what we buy brand new

off the shelf today - in fact, some of these "oldies"

are far better made, virtually indestructible, and will still

open any oyster in no time flat. Worn out, damaged or snapped

old wrenches and files seemed to be favorites for conversion

to an oyster knife. Image above: This old oyster or clam knife seems to have been crafted from some old carbon steel hand tool, perhaps a wrench or prying tool. The blade is finely beveled on both sides and very thin, the edges quite sharp. Although the extremely fine point took a little damage, an oysterman or blacksmith could have easily restored it on the wheel. However, it was not, perhaps due to the fact that the point is still more than adequately sharp despite the little chip. Dimensions: Blade 3 3/8". Blade width at center point 3/4" (~ 20 mm), narrowing up to the point and also back to the start of the handle portion. Butt to point 9" (~ 22.5 cm). Weight 11 oz. The blades on these oldies are frequently perfectly straight and, in some cases, surprisingly thin with very smart beveling. No doubt, dazzling displays of bright sparks showering from hand powered grinding wheels for many hours were common sights when oyster knives like these were once made.  Image above: Here's an old carbon steel shellfish knife from Massachusetts. I call it a shellfish knife instead of an oyster or clam knife because I'm not certain of its primary application. It may have been used in conjunction with various shellfish types (clams, oysters, scallops) and more than one opening technique. Weighing in at 10 oz, it is certainly a heavy weight. This unmarked knife is exactly 8 inches long. It probably dates back to the later part of the 19th century and was likely custom made locally somewhere in Massachusetts by a skillful blacksmith. The edges are finely beveled and rather sharp, the strong blade is very thin. Instead of narrowing, it widens from the handle. Its square steel bar stock design (usually about ½ x ¾") is common among many other knife designs once used up and down the East Coast and Gulf. Health advisory: There is a risk associated with consuming raw oysters or any raw animal protein. If you have chronic illness of the liver, stomach, or blood or have immune disorders, you are at greatest risk of illness from raw oysters and should eat oysters fully cooked. If you are unsure of your risk, you should consult your physician.

This site is maintained as an archive. Contact: |