Screwdrivers, Hammers, Pliers, and Better

Mouse Traps

John McCabe

What follows is an overview of a few ordinary hand tools used

by some folks to open oysters as well as a closer look at some

related professional and kitchen ware tools. Tools that are pulled

right out of one's tool box are entirely out of place when processing

food - particularly when preparing a delicacy like oysters. Besides

tools, a tool box frequently harbors residue from motor oil,

grease, rust, paint chips, tiny metal fragments, and lots of

other "incidental stuff".

* Screwdrivers

A flat-head screwdriver is likely the most common conventional

tool used to open oysters. It does work. Both the classic

method (entry via the hinge) and the clever

chipping method will quickly open the oyster. I used a skinny

flathead screwdriver for years. One fine day I skewered my left

hand with it. I choose to reflect back on that annoying week

during which my left hand was out of commission as a time of

enlightenment. I "brilliantly" deducted that the "screw"

part in the word "screwdriver" actually has something

to do with screws - not oysters. Ironically, up to that point,

I had always been the one to preach "Performing a good

job presupposes using the right tools." I then went

out and bought a good quality oyster knife - and later wondered

how I ever got along without it.

* Hammers

Besides the proverbial "when all else fails..." carpentry

claw hammer, there are several other types of hammers that are

certainly noteworthy in the context of oysters. All of them have

one thing in common: They are used for cracking and chipping,

never smashing!

Conventional (Claw) Hammer

In terms of opening oysters, the conventional carpentry claw

hammer is probably still the most commonly used hammer style.

This phenomenon may, at least in part, be due to what some might

have interpreted as a form of governmental endorsement of this

crude instrument as an "oyster tool" ("... a

method preferred by some cooks"). In 1964, the U.S.

Bureau of Commercial Fisheries issued a booklet on oysters. It

had been reissued numerous times since 1953 and was part of a

series of booklets on the preparation of fish and shellfish.

All of the booklets were  exceptionally well done. In the oyster booklet,

the use of a conventional carpentry hammer was shown for "billing"

the oyster (inset picture) and the subsequent use of an oyster

knife was advised to cut the adductor muscle inside. The clumsy

hammer is entirely superfluous (and one more tool to clean),

as a quality oyster knife will perform both tasks just fine (as

described in the clever

method).

exceptionally well done. In the oyster booklet,

the use of a conventional carpentry hammer was shown for "billing"

the oyster (inset picture) and the subsequent use of an oyster

knife was advised to cut the adductor muscle inside. The clumsy

hammer is entirely superfluous (and one more tool to clean),

as a quality oyster knife will perform both tasks just fine (as

described in the clever

method).

If, for some

reason, the use of this hammer type is deemed indispensable,

perhaps a small ball-peen hammer (instead of a claw hammer) might

be considered instead. The head of the hammer should be unpainted.

It should then be dedicated solely to food preparation purposes

and never end up out in the tool box. The face of the hammer

(not the ball end) is used. It may also come in handy for other

types of shellfish (like crab).

If, for some

reason, the use of this hammer type is deemed indispensable,

perhaps a small ball-peen hammer (instead of a claw hammer) might

be considered instead. The head of the hammer should be unpainted.

It should then be dedicated solely to food preparation purposes

and never end up out in the tool box. The face of the hammer

(not the ball end) is used. It may also come in handy for other

types of shellfish (like crab).

A so called cross-peen hammer is even better. It has

a horizontal straight edge (instead of the ball) on one side.

Both the face and the edge side may thus prove useful in the

kitchen.

A so called cross-peen hammer is even better. It has

a horizontal straight edge (instead of the ball) on one side.

Both the face and the edge side may thus prove useful in the

kitchen.

The so

called straight-peen hammer can also serve nicely in the kitchen,

not only as a crab or oyster helper, but also with tasks such

as breaking tough bone ligaments on meats. Unlike the cross-peen

hammer, the straight-peen hammer has a dull hatchet like edge

which runs in line with the handle. After use, hammers should

be washed and oiled with a little vegetable oil to help prevent

rust.

The so

called straight-peen hammer can also serve nicely in the kitchen,

not only as a crab or oyster helper, but also with tasks such

as breaking tough bone ligaments on meats. Unlike the cross-peen

hammer, the straight-peen hammer has a dull hatchet like edge

which runs in line with the handle. After use, hammers should

be washed and oiled with a little vegetable oil to help prevent

rust.

Crab Hammer (a.k.a. Crab Mallet)

Crab Hammer (a.k.a. Crab Mallet)

Crab hammers (frequently also called crab mallets) may be the

best hammer style of all in terms of seafood preparation. Usually

they are rather small. The round or square head commonly measures

about two to three inches wide and the combined length of the

tool amounts to approximately seven or eight inches. Besides

operating these little hammers with the handle, some designs

also allow using the head as an excellent grip, thus turning

their special handle into an additional tool.

The functionality of these little hammers

is certainly not limited to just crabs. Besides other types of

shellfish, they can prove to be a rather handy kitchen tool when

preparing quite a number of other foods.

Crab hammers can be made of a pewter alloy

(like the famed Wilton crab hammers), all hardwood, stainless

steel, or some combination of hardwood and metal. Pewter never

rusts. However, it is considerably softer than steel, even as

an alloy. Hence, the pewter handle should never be used as a

prying tool, as it may bend. Wooden crab hammers also work well.

They are comparatively inexpensive. Much like the wood of cutting

boards, they may expand and contract and ultimately crack if

left uncared for in a moist state. Since wood is porous, it can

also harbor bacteria and attract mildew. Hence, wooden crab hammers,

right along with wooden cutting boards, should be cleaned properly

after use with a light water/bleach solution (2 parts water and

1 part bleach) and dried. Some of the wooden designs also feature

a convenient hatchet like edge on one side (similar to the straight-peen

hammer pictured further up in this text). The handles are round

and functionally serve no purpose other than what is expected

of any typical hammer handle.

Most metal crab hammer designs work particularly

well on oysters. Besides using the head in a chipping or cracking

manner to create an opening along the edge of the oyster's bill,

it can then switch to being the handle of an effective blade.

This "blade handle" can then be inserted in the opening

to cut the adductor muscle within the oyster.

Image left: An older crab hammer with a pewter

sleeved hardwood head and a stainless steel handle. It was made

in Japan (perhaps in the 1960s or 70s) without a manufacturer's

name. It has a crab imprint which is identical to the one used

in the Wilton pewter crab hammers (pictured above). Although

the shape and size of this crab hammer is almost identical to

the commonly found American pewter hammers, it is considerably

different. The head is made of some type of hardwood which is

sleeved by a pewter band. The "handle blade" is made

of fairly thick stainless steel with tapers down to a rather

dull, flat and rounded tip. Aside from being rather attractive

looking, it is also one tough tool - much like an oyster knife

with a "T" handle. A large oyster can be billed and

shucked within seconds with this particular fellow - without

ever using the hammer head. I don't bill oysters with the handles

of pewter crab hammers. Pictured ruler measures in centimeters.

Hammer length 17 cm or 6 3/4". Head width 5.8 cm or ~ 2

1/4". Head diameter at ends 2.6 cm or ~ 1". Weight

5 oz. Dimensionally, the famous pewter Wilton hammer is quite

similar. The older one I have has a length of 16.5 cm or ~ 6

1/2". Head width is 5.5 cm or ~ 2 1/4". Head diameter

at ends 2.6 cm or ~ 1". Image of an older Wilton can be

viewed by clicking here.

Image left: An older crab hammer with a pewter

sleeved hardwood head and a stainless steel handle. It was made

in Japan (perhaps in the 1960s or 70s) without a manufacturer's

name. It has a crab imprint which is identical to the one used

in the Wilton pewter crab hammers (pictured above). Although

the shape and size of this crab hammer is almost identical to

the commonly found American pewter hammers, it is considerably

different. The head is made of some type of hardwood which is

sleeved by a pewter band. The "handle blade" is made

of fairly thick stainless steel with tapers down to a rather

dull, flat and rounded tip. Aside from being rather attractive

looking, it is also one tough tool - much like an oyster knife

with a "T" handle. A large oyster can be billed and

shucked within seconds with this particular fellow - without

ever using the hammer head. I don't bill oysters with the handles

of pewter crab hammers. Pictured ruler measures in centimeters.

Hammer length 17 cm or 6 3/4". Head width 5.8 cm or ~ 2

1/4". Head diameter at ends 2.6 cm or ~ 1". Weight

5 oz. Dimensionally, the famous pewter Wilton hammer is quite

similar. The older one I have has a length of 16.5 cm or ~ 6

1/2". Head width is 5.5 cm or ~ 2 1/4". Head diameter

at ends 2.6 cm or ~ 1". Image of an older Wilton can be

viewed by clicking here.

* Other Hammers

Culling Hammers

Culling Hammers

Culling hammers are not used to open oysters. On the contrary:

They are precision tools used in a process called culling, the

skillful and delicate work associated with separating individual

oysters from oyster clumps. More on culling hammers in the commercial opening

section.

Crack Hammers

Small, all carbon steel hammers called crack hammers were once

used in some commercial shucking houses to knock off a piece

of the front of the oyster (the so called bill) to more easily

gain access to meat inside with an oyster knife. Frequently a

special "cracking block" or "oyster shoe"

held the oyster in place. A so called crack knife was

also used in this process (pictured under knives).

Crack knives are heavy. They were machined out of a piece flat

carbon steel bar stock (usually about 8" long). The handle

ends of these knives, where the crack hammers impact, are the

flat ends of the original steel bar stock (usually ½"

x ¾"). Today, the commercial use of crack knives

for opening oysters is considered an occupational safety hazard.

*

Pliers

*

Pliers

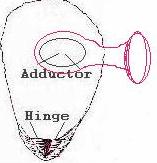

The use of a pair of pliers to open an oyster is also recommended

by some folks. Unlike the "hammer method" which addresses

the side margin of the "bill" in the government booklet

mentioned above, the pliers are applied to the front of the bill.

An attempt is made to snap off a chunk of the upper and lower

shell halves and create an opening where a knife can then be

inserted to cut the adductor muscle inside. Although it does

work, it can be a real pain in the "you know what"

on large oysters. Since oyster shells, particularly large ones,

are remarkably tough, it is best to "nibble away" pieces

until a sufficiently large hole  for the knife blade is evident. Essentially,

the "pliers method" is a clumsy variant of the commercial method,

as the commercial method also aims to remove a shell chunk from

the front of the bill - with an oyster knife of course, not a

pair of pliers.

for the knife blade is evident. Essentially,

the "pliers method" is a clumsy variant of the commercial method,

as the commercial method also aims to remove a shell chunk from

the front of the bill - with an oyster knife of course, not a

pair of pliers.

"Better" Mouse Traps

"Automatic" Lever Action

Devices

A review of clumsy oyster opening methods would not be complete

without mentioning the "automatic" lever action oyster

openers. To the best of my knowledge, various models of these

devices started popping up in the market place in the 1970s,

probably right about the time Dan Aykroyd presented the truly

amazing "Bass-O-Matic" on the Saturday Night Live TV

show.

The device pictured is called a "Safety

Action Oyster Opener". Not included: The pen, merely for

size reference, the screw driver (we'll get to that), and the

victim (a medium Pacific oyster). It features a varnished wooden

base measuring 5 x 7". A groove, approximately 3 ¾"

long, 1" wide, and ¼" deep was hollowed out

lengthwise. An upside down V shaped bracket (about 3 ¾"

tall, stainless) in the forward section, mounted on the wood

with two ¼ hex head screws, serves as the hinging sector

for a flat stainless bar with a round wooden handle on the end.

The bar is about 1/32" (1mm) thick and approx ¾"

tall (handle part 1 ¼ x 3"). The bar and handle measure

about 8 ½" long and hinge on what appears to be a

brass alloy rivet at about the 2 ½" mark on the upside

down V bracket. A strong steel pin with a point, about ¾"

long is welded to the rather thin bar, on the underside and perpendicular,

just short the half-way point between the bracket and the beginning

of the handle. With the bar held up to where it is positioned

horizontally and parallel to the base, the point of the pin aims

at the hollowed out groove below at the beginning of the forward

1/3 of the groove. This is where the oyster will be pierced by

the point of the pin, hopefully right between the shell halves

while it is held down on its edge in that wooden groove. The

entire nifty device comes in a 9 ½ x 5 x 5" box and

includes an interesting piece of paper titled "Directions

for use".

Action!

Action!

The "automatic" oyster opener immediately charmed me

with its obvious mechanical simplicity and I was most anxious

to put it to work. Although I suspected the use of it to command

little more intelligence than required to operate a conventional

paper cutter, I decided not to fall victim to the old adage "when

all else fails, read the instructions". I'm glad I did.

I was instructed to position the oyster on the base in that groove

and to bring that point down on "any of the three sides

away from the hinge end… It is important at this stage to

probe these three sides for the true dividing line between the

shell halves. Nature has provided the oyster with a series of

apparent edges or dividing lines, only one of which is the true

one. Practice makes perfect." Hence it did not matter

if that point pierced the shell divide on the side of the adductor

muscle, on the bill, or the side away from the adductor. I was

then advised to apply firm downward pressure on the handle with

the opener point placed at the "most likely line"

between the shell halves. Either the oyster would then open rather

easily or I would have to try again until I find it. Bottom line:

That part does work and the pin indeed pries open a gap between

the shells. Now what? The adductor muscle of the oyster is still

hanging on for dear life and the hinge has not relented. Another

look at the instructions furnishes the answer: "As soon

as the two shell halves start to separate or shift sideways under

pressure from the opener, insert a common screwdriver into the

opening and with a twist of the wrist(,) hinge will break and

oyster will be open." The oyster essentially ends up

being ripped apart by the shell halves - not elegant by any stretch

of the imagination and certainly not very automatic. Despite

appreciating the irony at hand, I didn't really like being asked

to go out and look in my dirty old toolbox for a "common

screwdriver". I thought the screwdriver days of opening

oysters were over. This new "thing" was supposed to

open the oyster. I don't need that "thing" because

I already know that my flathead screwdriver alone will open any

oyster via the hinge. Needless to say, I will try to resell this

device at my earliest convenience as "only used once".

Pull Tab Oysters

Pull Tab Oysters

A couple of years ago I ran across a European news blurb advising

of a new way to open oysters. Some enterprising guy had figured

out a way to insert a thin piece of stainless steel or nylon

wire between the shell halves of a living oyster, then somehow

loop it around the adductor muscle and then feed it back out

of the oyster. The ends were then tied into (or attached to)

a loop or pull. Lots of fresh oysters with convenient little

rip chords hanging out of their shells could then be offered

to the public. The design is somewhat reminiscent of pull tabs

on soda pop cans or a garrote of some sort. All the consumer

needs to do is yank on that loop which then cuts the soft adductor

muscle inside the oyster and - voilà! - it's open. Oyster

knives would be rendered obsolete. Well, actually not quite obsolete

as the rip chord would certainly sever the adductor muscle, yet

leave at least one substantial portion of the cut adductor muscle

firmly attached to the shell. Hence it would first need to be

cut from the shell before the oyster would be ready for slurping.

I'm not sure if the idea ever caught on. I suspect it did not.

Update (Jan. 12, 2008): Looks like the

oyster pull tab idea is still alive in France. Picture of one

of these "pull tab" oysters: https://www.dzigue.com/images/magic-huitre.jpg

French website describing this "oyster magic":

https://www.magic-huitres.fr/catalog/